Log Entry #2, December 2009. Stabilizing.

Summary: The life continues to be very inward-looking as we strengthen the vessel in preparation for going back to The Baja. After a short visit to La Paz we plan on taking a break through January, then continuing along Ulloa's route north. Interestingly, Ulloa and his crew broke their rigging, somewhere around Puerto Vallarta. Strangely, so have we. Fortunately our problems are nowhere as severe.

Please note that this is part of an on-going series of log entries that will be posted monthly. Visit the contact page if you'd like to get updates.Before we get started on what happened with The Blue Goose, I have some Notes On Ulloa that need to be put down:

04 DecemberAfter searching in the libraries of La Paz, New York, San Diego, Mazatlan, and Puerto Vallarta and the skimmings of the poor data of the Interwebs, I've discovered some logbooks of interest. There are many lines and individual words that are missing from them. Most of this seems due either to salt water that arrived on the hand-written pages, causing oxidation of the inks, or something like coffee or oil that created a smear or simply obscured the writing. In any case, despite the author speaking to us through an ancient, stained and tattered window, his gestures are still clear. Ulloa's voyage remains one of discovering an era more than a land.

With an exception, I will leave the history of Cortez and the conquest of the Aztecs to another work. But one thing must be recorded here, which I've found to be strange and so extreme that I can't overlook it. It amounts to the following.

Hernan Cortez, a conquistador with a definitively quixotic streak, arrived in Cuba (let's say Hispaniola) during that last decade of the 1400s. This was just a few years after Colombus had arrived in Florida. Cortez took it upon himself to lead the third expedition up the eastern coast of what is, today, Mexico. After finding some translators he discovered a land that was in a bit of turmoil. The Aztecs, who had conquered central Mexico with rapacious violence, had made some enemies. So with his translators and some powerful and very pissed-off tribal leaders to help him, Cortez walked with horses and guns to what is today Mexico City. There, on a small island in the middle of a lake rimmed with floating gardens and high pyramids, he met with the king of that land, named Montezuma. Montezuma, in his late 30s, or thereabouts, had spent much of his life as a high priest in the Aztec church. Cannibals and hierarchs of the highest order, the Aztecs also had a highly refined sense of civilization (it was the Spaniards who did not wash themselves), and because Montezuma had served as a priest of the Aztec church prior to becoming their king, he knew the prophecies. Part of the historic writing of that church indicated that time functioned in a kind of circle. Time was a loop and events repeated themselves. One of the events that would repeat was that of a group of men, coming from where the sun rises, would conquer the land. These men from the east, each time they arrive, wear hard silver clothing. They have white skin. They have beards and ride large deer. So naturally, when Cortez and his company arrived, bearded, white-skinned, dressed in steel, riding horses, Montezuma had little choice other than to invite them in. If fate herself knocks, you have no choice other than to open the door.

History, in Mexico, is not a river. It is a whirlpool.

To make an intricate and interesting story something short enough to eat in one small bite, the Spanish, after conquering Mexico, decided to push north into what is today California. California (the name itself has a legend that is hardly believable, including a tribe of naked black huntresses, much gold, no men, and other such imaginings as only Cervantes has popularly described) would be explored. The conquest must continue north, into this mythical land called California.

On a sunny July 8th, 460 years ago, Acapulco was a small sea town with only a couple hundred persons living there, many of them Spaniards that had recently come over from Europe to try their hand at doing anything from trading slaves to raising oranges.

There were three ships that set sail that day, leaving the bay of Acapulco for a unique voyage north. First was the Santa Agueda (~120 tons), a three-masted kestrel, a well-built vessel, I've heard, and the largest of the three ships. The second was The Trinidad (about 30 tons, with two masts), and the third vessel was the Santo Tomas (which was only 20 tons, just a little larger than my own ship). Since the Santo Tomas was so small it only needed three or four hands on-deck, plus the skipper, who was named Manuel Alfonso. With the fleet were three Franciscan friars: Fray Antonio de Meno, Fray Raimundo (maybe named Anyelibus, the records are not impeccable and are badly damaged in some places), and Fray Pedro de Ariche. The ship pilots were Juan Castellon and Pedro de Bermes. And, as I have said, Don Alfonso.

At the head of the fleet was the director of the expedition, Francisco de Ulloa, who had been commissioned by Cortez to discover this mythical land of California.

The mission's goal was to examine the coastline of the mainland as far to the northwest as possible, simultaneously looking for a safe and easy route to Asia. While Cortez was in Spain one of his competitors, and a fellow conquistador, Nuño de Guzman had pushed an expedition north and gathered local knowledge, hearing news of a spit of land we now call Baja. But despite these rumors Cortez decided to explore it for himself. Additionally, and most likely there were two alterior goals. First was proof that there was land there. In 1533 a two ships sailed from Tehuantepec to La Paz. Cortez claims to have been on one of these ships. The expedition left with several hundred people and arrived shortly thereafter in La Paz. After setting up a small colony the locals killed many of these people (the colony eventually collapsed from starvation and dehydration) but proof of "California" had been engraved. De Guzman fully expected to find the kingdom of the Amazons a little north of the Rio San Pedro (in today's New Mexico or Arizona) at a little town called Astatlan. Second were dreams of gold, babes, and glorious battles. Like all good conquistadors his head was full of books. This one, in particular, was the The Exploits of Esplandian (Las Sergas de Esplandian) by Garcia Rodriguez (or Ordonez) de Montalvo, first printed in 1510. This romance was the outcome of De Montalvo's translation of Amadis of Gaul. In the story, Esplandian, the son of Amadis, has many strange adventures, among which is a meeting with the Amazons. The name "California" appears in many passages of the book -- for example, Sergas, chap. 157:

Know that, on the right hand of the Indies, very near to the Terrestrial Paradise, there is an island called California, which was peopled with black women, without any men among them. because they were accustomed to live after the fashion of Amazons . . . In this island called California are many Griffins, on account of the great savageness of the country and the immense quantity of the wild game there . . . Now, in the time that these great men of the Pagans sailed (against Constantinople) with those great fleets of which I have told you, there reigned in this land of California a Queen, large of body, very beautiful, in the prime of her years....

And with such dreams to keep things so excitant, the little fleet set sail north, up along the Mexican coast, in fair weather, the unblinking sun smiling. For eight days all seemed favorable. The barometer registered high and healthy. The winds were gentle. The skies looked clear. The sun set and the moon rose and all seemed simple. But underneath the keels of these three vessels the gods of the sea cracked their knuckles and chuckled. Fair weather it was not to be.

Sometime just before morning of the 16th of July, a Wednesday, about four hundred miles up the coast, the little fleet was hit with a hard storm. The winds turned into knives, sails were stretched and then ripped, waves washed aboard, masts were broken, and onto the deck and into the dark sea they fell. There are eight lines missing from the ship's log. But it appears they used winches to then recover the masts and sails and other things that had been, literally, pulled into the sea by the waves and winds of a terrible and ferocious night.

I made a new logbook page for The Blue Goose - it reminded me of making a character sheet for D&D, only better.

If you happen to be a sailor, or interested in visual details, it is here (click image to download the PDF or the InDesign file):

05 December

Near Punta Monterrey, just a few miles north of Sayulita, I caught a skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) that weighed about 15 pounds. He should be good for dinner and we have lots of limes so he'll also be good for breakfast and lunch and a ceviche tomorrow. Tuna are interesting fish to catch, and you tend to know when you have one, as they hit the line really hard and then dive deep shortly afterwards. The skipjack tuna are beautiful bright blue fish who have no scales, except for around the pectoral fins. They eat squid, crustaceans and other fish of course. So many of them have been killed in the last 50 years that I wonder when they'll be endangered. Fishing stocks around the world have fallen 80% in the last 50 years, and that's including improvements in their methods, like using helicopters to round them up (they're easiest to see at night, because the schools leave phosphorescent light in the water that can be seen from a helicopter).

Anyway, I don't catch much and generally only think about it when I'm tying a line. I use a Rappala lure which looks, oddly, like a little skipjack - only about as big as my index finger - so that I'm sure to get someone rather large. They're fished often by the Mexicans, but I'm always happy to get one, instead of a yellowtail, say, as there's still many of them in the water. As soon as I pull him into the boat I cut his spine as quick as you can snap your fingers. One of us usually say some kind of prayer, a simple thing, like "Thank you little fish" because we appreciate his life and we plan on eating him. We call him "little fish" when we say this out of affection, even if just ten seconds before one of us yelled, "He's a big ole boy!" Our affection and appetite seem in conflict.

There are some fish in these waters that are bigger than me. I saw a swordfish in the back of a panga that was easily 3m long and must have weighed over five hundred kilos. If I caught one of them I'd probably get the machete and we'd really have something to yell about. Fishing is exciting because it is bloody.

06 December

It rained last night, and we knew it. First it rained hard and with large drops and woke us up because it was like a mob of miniature monkeys were slapping on the boat. Then it backed off and hissed rain until dawn, at which point it is now a mere fog. This all would have been fine had it not been for the leaks. We did our best, two months ago, to re-caulk every crack and fissure and joint and barrier-seam we could find. It involved about two weeks of replacing gaskets and masking over what was not to be replaced, then cleaning and sanding and scraping and re-cleaning and mixing and then filling each of these various holes in with fiberglass or 4000 or 4200 or whatever damned toxic chemical the various hole hungered for. But, despite all our efforts, and even re-caulking the forward and aft hatch twice, and with best advice from the dock consultants, we still had a leak, which I think was because the 4200 we used (some of the dock consultants recommended sikaflex, yes) was susceptible to UV exposure, and so shriveled, and let water in.

The water did not get into the bed. It did not, as it has many times before, fall on my face and wake me to its arrival. No, I had the dinghy upside down over the forward hatch and so the bed stayed comfortable and dry, and a little dark. But the water came in nonetheless and when I woke, and rolled over to look at the boat for the first time today, the floor was smooth and shiny, and I knew it was not because of a new varnish job.

There may be leaks where the spreaders touch the deck, but I think we're tight. Most of the work we did seemed to help, but the hatches - the skylights - are definitely leaking and the water then comes in along the curved ceiling and falls down the walls.

Old salts have told me, "Oh, it's a boat. Get used to it."

Over the years my little collection of books have absorbed enough water that they gradually found their natural form again and seem to be returning to the forests from which they came. Sailors, after all, aren't known for being bookish.

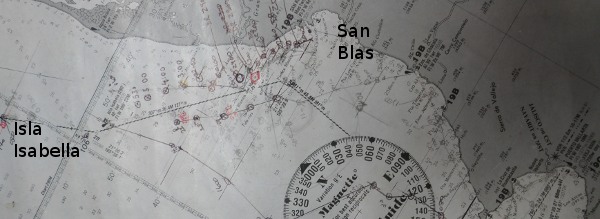

After surfing for a few hours on some beautiful, nearly kilometer-long waves in Mantechen bay, where dolphins swam under my board and looked up at me as they did so, and after eating a solid dinner of posole and tuna, we left San Blas at sunset, motored out with the setting sun and when the wind came up so did our sails to catch a ride west, towards Isla Isabella.

07 December With the prow slicing through the waves that were mostly against us, Amelie went to sleep and left me at the wheel for my shift from 11-2am. The boat began to rise and fall, waves coming directly against us. We'd entered the California Current, which I think of as one of the arteries of the Pacific, a great circulation that carries both plankton and plastics down the coast of North America, along the Baja, and out into the still waters along the equator. As we entered the waves the boat began to bob and trot and all seemed quite progressive and positive until I noticed that the backstay was banging around. The backstay is the cable that runs from the top of the mast to the aft-end, or, well, the back of the boat. This trembling and slack in the backstay meant that the mast itself was angling forward and aft, a good foot or two, perhaps, at the top as the boat climbed a wave and then descended. Holding my hand on it I noticed that the boat, too, trembled with these movements, the pressure of that great shivering being transmitted through the hull.

The problem continued and after a short investigation with a headlight on the head and a foot on the wheel, so I could properly get my head down near the motor to investigate, I discovered that our hydraulic pressure system, which cranks the backstay tight, was low on hydraulic fluid and, being some 15 or 20 years old, had popped a leak. There wasn't much to be done, so I tightened in the foresail and continued to wind, through the opposing waves. Eventually Amelie took the wheel, I took the pillow, and by my next shift Isabella was in sight. We arrived with the sunrise and caught a little bonito shortly before we arrived.

08 December

Isabella is the best of what I've seen of the Mexican coast because there is no development. There is no progress on Isabella. There is no airplane strip, no roads, and only a building and a tent where some researchers occasionally come. Two massive towers of stone lean out over the water, and these twins face east, towards land, as if fending the island from civilization. We anchor just below these columns of stone in a sandy shoal that's there, and when evening comes we crack a beer and stare at the birds. Isabella is a bird sanctuary, and so the constant screaming and slapping and splashing around the boat is part of the day's entertainment.

It is an avian metropolis. One resident of the city are the winged frigates (relatives of the pelican who happen to have the largest wing/body ratio of any bird and look like tiny dracula-hawks as they fly on high). Frigates can't touch the water. They're excellent fliers, and despite spending their entire life at the whispering sea's edge, they can't enter it. Another resident is the Booby (a bit like a seagull, they live on the ground, also at the water's edge, and some have blue feet and some red or orange). Boobies float over the water and when they see a fish they become a little missle and nab the fish and then come to the surface with it. This is when Frigate, who noticed Booby diving, descends fast and tries to take his food. But Booby is fast and launches himself from the water, but Frigate is faster, and can catch Booby. So Booby returns to the water, fish still in his mouth, making muffled squawks as Frigate tries to get close enough to take his food without hitting the water with his wings. If Booby flies, Frigate will chace him until he pukes, and then eat that. Like in any city, with any system of commerce, we all do what we can and what we have to.

At the foot of the two large towers, in the water, hovers a silent city of fish. Thousands of them, all in a mobile state of feasting, like little legless floating pigs, carouse the coral and eat all that can be sucked, knocked, chipped or chewed free. They each follow one another in a mostly silent congregation - for they do make some small noise from time to time, a click or a grunt, but it is very hard to hear because you have to be still and waiting for it and it has to come when you are not breathing through some pipe or other, only while truly holding your breath and waiting for it - and each keeps a watchful eye on the Boobies above, and cluster around their neighbor who happens to have found interest in something, or simply turned. Of course they have to watch for the diving Boobies from above. When I jump into the water they scatter, and then come back close to do what seems the equivalent of sniffing me. They don't have much fear of humans, nor a boat at anchor.

I put on my goggles and jump off, to dive the boat. She has a thin green film that accumulates along her hull after a few weeks, a slightly slimey growth, which I'll have to wipe off. There's a couple tiny barnacles that have managed to click and hold, building their chitinous mountain-shell on our mobile home. I pick them off with my finger. Then I notice curious zigzags that go up and down the hull, slashes of lighter color that are only about as long as my hand, which go left and right and then back again, each one the same methodical distance, as if someone came with a paintbrush and drew zigzag patterns in a lighter color. It is so precise in it's breadth, and so direct in its verticalality, that I wonder if it is the effect of something with the construction of the boat. In the way that cracks will follow the lines of a building's construction, I wonder if these mechanical W's are some hull lay-up artifact. Then I notice that these W's are where the slime has been removed. It was one of those piggish little fish, finding breakfast.

I pick off a few more barnacles, leave the boat dirty, and climb in. We have a solar shower, just a bag of water, and I use that to wash the salt off. After I get dressed I bite into an apple and get to work.

We spent the day at Isla Isabella resting, working on normal work-stuff, and slept that night in warm winds of 20-30 knots. Being a hundred or so miles off the coast, anchored to a sandy island full of wild birds overhead, voracious fish below, and watching the sun rise and then set and smelling the air and still having the comfort of your home inside is nothing if not magnificent and disconcerting. It is magnificent for obvious reasons. It is disconcerting because it is the ocean. Imagine living in a normal house or apartment and having a sky that, at any time, might turn red and fill with winged monkeys, or a ground that might turn purple and suddenly, in a day, heave up into an earthquake, and you hear the howling of the monkeys outside, and if you go out onto the balcony or porch you can see the land rippling and heaving, and then when you go back inside you hear the building creaking and feel the movement. But you're safe. This is what a boat is like. Living in a magic world, with danger at the doorstep and the security and safety of home inside.

Provided, of course, you tend to the details. In a way there is a balance. On one hand you have the winged monkeys and earthquakes outside. Those that would enter or break down your foundation. But on the other hand, on the inside, you have the small swarm of repairs that crawl over everything; a crack here, a leak there, a piece of rust or water coming through an old seal. This swarm of repairs and maintenance present a smaller danger, inside. It vacuums the days and sucks up the hours and after a week I often look at how unproductive I've been and my jaw falls open, counting on my fingers the number of hours I spent working on the boat, I generally arrive at something around 20. It is a part time job, just batting at these small repairs. But this is at least half of sailing, because in batting at the repairs I chase them from the home and there they surround the boat and form a wall and keep at bay the flying monkeys and maroon earthquakes.

09 December

We raised the sails and left isabella at about 8am. It would be a good 24-36 hours before gaining Mazatlan's ground and much of it would be through the California current. At about 10am we caught a little bonito, only about as big as my foot, and threw her back. Then another, which was also tossed back with but a hole in the face. Then a small mahi-mahi, only about as long as my forearm, and only about as thick, which we threw back, too. Small children-fish. The lure was, after a good years' use, starting to show some wear. There were fish teeth-marks all over it. Tiny little gouges where our victims had tried to sink their own barbs, but found it harder than they had expected. I imagine that the equivalent of being a fish, and being caught, for a human, would be to go into a restaurant, McDonald's say, and order a big mac and put it on your tray and get a coke and put your straw into it and sit down at the little table, and bite into the thing and then be dragged, by your face, out the window.

We continued to draw attention and by noon the strikes stopped and I had started to think about pulling the rod in when the rod was pulled out. Faster than a flash, with a great clank and slam, the entire rod jumped out of the back of the boat and splashed into the water. I considered diving in for it, knowing Amelie could handle the boat and come back to get me, but the rod would sink faster than I could clear the distance to get to it and the fish that pulled that thing wasn't going to stop pulling any time soon. The fast-fading bubbles slowly disappeared and then we saw a magnificent and mammoth fish jump, about 20 meters away, a huge bull-headed Mahi-Mahi, as big as my leg, thrashing confused, flashed in the sun then disappeared again into the waves. I didn't feel great about losing my rod and the little Rappala poisson mechanique, and I felt a lot less good about hooking him unecessarily. Evidently, those hooks rust free in a few weeks, so he might be able to make it (though the fishing line will take 600 years to decay). Seeing him flash like that, jumping, trying to get himself unhooked left me alert to the cruelty of fishing.

Anyone that tells you that fish have no feelings is a human that has no brains; pain is one of life's essential ingredients.

11 December

We got our FM3 visas, so we are good to stay for a while longer. As long as we can re-proove that we make a little money (bank accounts were required), have an address (the marina did the job), and carry legitimate passports we can stay. I considered working, as a delivery skipper, here in Mexico, but the concept of being an illegal alien, working, seems spooky. I've seen far too many Mexicans get in trouble in the states, and I suspect I would not be treated kindly if I were to try to skate under the wire and got snagged up in the process.

13 December

|

At dawn, as I walked along the docks, coming back from the bathroom (an inexorably long walk, at times, if you happen to have to take a shit and also have to walk about a quarter mile to do it) I noticed that all the cats that live along the docks of Marina Mazatlan were staring, wide-eyed awe, at something up above my head. It was an old buzzard, a big one, watching me, and it made me wonder if I'd gone too long without a shower. I went back to the boat, got the camera, and took a shot, but by the time I'd come close to it he'd flown away.

Following our rule that we cannot be in a marina for more than three nights, and since today is our last day, we finish repairs on the boat and go. The backstay is the biggest problem and one we want to fix now, while here (leaky hatches can be fixed at anchor). So we took the thing apart and found a leak at the base of the pump. Taking that apart we discovered that we could not patch it, so we instead scrounged some #10 hydraulic liquid - a petroleum oil, really - from our kind neighbor Otis, threw some more oil in there and, planless, sailed out of the marina. We anchored at Bird Island - Isla Parajos - that night. |

|

16 December

Stone Island. Five miles south. The days have been work-related, getting work done on my manuscripts, doing some illustrations (two commissions came this month and an old friend also purchased two prints). But while working in the boat it was less-than-soothing to hear the mast wobbly and something creaking. This happened at sunset and rather than mess with the thing I decided to take a picture instead.

17-20 December

Finding balance on a boat is not a simple process because if there is not sailing and repairs to be done there is life, itself.

Work, Work, Work, making progress and making money, then my computer stopped. One thing if not then the other. A friend once called me "the man that rides the broken machine" but that was in college. This concerns me today, years later. I am not one for machinery. I hate it and so I try to neglect it. But the boat and my computer will not allow such. Despite unhinging myself from most infrastructure, some I cannot entirely leave behind. I'm human, afterall, and I guess that being connected with infrastructure is part of what makes us such.

Anyway I managed to upgrade the computer into a coma. Four days were spent learning how to reconfigure the video portion of linux kernels (Linux, and Ubuntu in particular, is fantastic, but I now hate Nvidia nearly as much as I hated Microsoft because their drivers are not being made public). I finally abandoned it as work is loading up. This is not comforting. The mast is wobbly and the kernel is cranky.

There were two beautiful evenings we spent at Benji's, with our good friend Ely, (who recently married Anita, a Mazatleca, con zapatas salidas, and they have a baby coming in a few months). We drink beers and eating shrimp-garlic-ham pizza, or an occasional foray into the old center of town for some smoked marlin, tomatoes, and a bottle of water. But mostly we're on the boat, working.

Still at anchor, still working hard, 16-hour days still preventing me from touching the rigging, just dumping the last of the oil Otis gave us into the canister and hoping no damage is done. I can't see any way possible something happening as interesting as the mast coming down, but there is wearing and tearing happening because the system is moving in ways for which it was not designed.

On Sunday, the 20th, I took time off and we paddled the dinghy out to the south side of stone island and I dove and found an oyster and in it I found the concept of adaptability, the opposite of the shell.

21 December

I finally found a window free from real-work this morning, so I called about to find what we needed to do to repair the pump. It's not a big priority, this pump. It is for racing. It's for cranking the mast back into a tenuously tight angle so the boat can sweep faster upwind. We can take this damned thing out and put in a stupid turnbuckle for about $50. But I'd rather repair than simplify, especially since I have no idea how to sell a used hydraulic backstay pump. Nor want to. So when I call around and find places in San Diego that tell me they can repair it for $450, I'm starting to think that turnbuckle is the way to go. But then our buddies at Total Yacht Works, and again Jorge Rosete, who worked with us on our arch, both refer us to a gentleman named Ernesto. So we call Ernesto, ask him to meet us at 3 that afternoon, off the docks. He said he would be there. I did not know what to expect from a guy that did hydraulic repairs.

By 3pm we were standing near the docks. The pump was in Amelie's lap as we sat next to the fence.

And the docks, because there are no women there, or at least in part due to that, get sketchy. Large dark men with hard hands growl around with cigarettes sticking out of a scowl, massive rusted boats slowly get leashed into a dock, pangas buzz around like flies near such behemoths, and we stand quietly on shore, our little pump in our little bag, our little problem seeming insignificant next to such large boats. We wait for about 15 minutes and a pickup truck parks next to us. Two unsmiling men, both dressed in matching blue short-sleeve button-down shirts, with the top button snapped tight at the neck, with a little white logo of a boat on the breast, approach us and, still unsmiling, shake our hands. They're grim like the mafia. Ernesto says he can have this back to us tomorrow.

Though they never smiled the entire time they seem to have some kind of sense of humor. I wondered, as they drove away, if they started gufawing and slapping the wheel, laughing about our spanish or something. They were so serious it seemed a joke. I like them alot.

22 December

9am and we call to confirm we're good to meet and they tell us that all looks good, and the pump is fixed, and that it will be $1500 pesos. We have $1000 pesos on the boat, so we confirm "mille cinqo ciento" and they say yeah, and we say we'll need a lift over to the ATM, and they say fine, so we hop into our little dingy and paddle to shore.

10am and Ernesto and his colleague show up. Grim, again, they hand us a plastic bag with old newspapers wrapped around the pump. They tell us that a man drove up from Culiacan to bring along the gasket, because it was a specialized kind of thing and they explain that it was just worn gaskets and they give us some oil we can use for it - a pint - and we hop into the back of the truck and head over to the ATM. taking out pretty much the last of our money, we hand them the 1500.

They hand back $1000 and ask for 50 pesos. We blink. They say, "Five hundred fifty, not one thousand five hundred." We hand them fifty, then fifty more as a thank you. This is about 10% of what the 'repairmen' in San Diego wanted to charge us. Ernesto and his boys did the work in the same day, for a tenth the price, threw in a pint of oil, and never broke a smile.

Back at the boat, we plug the pump in, start pushing on it, but nothing happens to the rigging. It should be tightening up, but ain't. I download some hydraulic testing manuals, bleed the lines again, check to make sure all is solid and as Amelie works on the pump I pay attention to the cylinder that is attached to the backstay.

Nothing.

So, the deal seems to be that there is a problem, now, with the backstay cylinder. The pump is surely working - I can feel pressure stacking up in it - but that pressure is not getting transferred to the cylinder that pulls the cable that pulls the mast back. It is at this point that I begin, again, thinking about the turnbuckle, but Ernesto was so fun to work with, so funny because he and his buddy never smile, that I think to go ahead and repair both parts of the system (after all, we're already into it for $50).

The problem here is that now I have to remove the backstay cylinder. This is not a simple operation. It means that I'll have to disconnect the cable that ties the mast to the back of the boat. Well, I think about old Ulloa and, grabbing our longest and strongest rope, I hand the two ends to Amelie and dive, with the center of the rope, under the boat, holding it there on the front of the keel while she takes up the slack. In this way we have the two ends of the rope, secured, and coming up into the back of the boat. We tie these to the backstay, remove the cylinder, and find that we can't tell a damn thing about it. There's an air pump and the place where the oil goes in. Oil comes out of both. I guess that's how it works.

Friends call to us from the beach. We take a break, get into the dingy, have a couple of beers with them, then return to the boat.

It is getting towards sunset and it has been a big day and I have absolutely no clue what to do with this thing and it is of utmost importance that it be reconnected because if the winds blow up some waves I don't want to have the mast fall onto the forward portions of our deck, so we simply put the cylinder back in, and again call Ernesto for help.

23 December

8am. Pulling the anchor, we motor from the little bay at the island, over into the harbor, and drop anchor there, with the other sailboats.

9am. Ernesto and I meet on the dock (I've rowed in) and we get a taxi to carry he and I to the Blue Goose. The dinghy is with us. It takes Ernesto a few minutes but when I tell him that I saw oil coming out of the air valve he says, "Oh, well you have a broken gasket in your cylinder. There is not supposed to be any oil where the air goes." As he looks at me he does not smile. He blinks and as he does so the world becomes less mysterious. each day. I hope that this means that the day I die all the mysteries will be solved. But doubting this I look at Ernesto and ask what it would cost to fix this. $150. fifteen hundred pesos. We have no money in the bank, I think, looking at the unsmiling eyes of Ernesto. We have some $20 or $30 for his time, now, but that's it. Some money for food.

When can he get it back to us?

"It'll only take about two hours. So I can get it back the same day."

While Amelie talks with him I go over and pull the anchor, flip on the motor, and we head slowly over, between the other boats, to the dock where I met him.

We ask what he wants to charge us.

"No charge. I didn't do anything." Earnest says (with unsmiling earnesty).

By luck and internet, a paycheck for some work from two months ago appears at the bank. We head in for the night, watch the movie Avatar, eat tacos, and get drunk on cheap beer. The neon lights are holy and I realize I've almost missed the city. Almost. It stinks, however, and the people seem to have lives more pointless, even, than my own, as if all people that are living in such a rooted, clustered, networked, and branching society are even more adrift than we. It smells like cars, an acrid smell that sits in the back of my throat, along with the stench of sewage and the beer I've had. The ocean airs are becoming preferable.

24 December

|

07:00. Despite being hung over, I'm getting better at disassembling our rigging. Rather than dive under the boat and use a rope to pull the top of the backstay down, I simply take one of the cables that we use to haul our sail to the top of the mast, and tie that off to the chainplate that is attached to the transom. So instead of adding a rope to pull up, I use what we already have to pull down. Less effort and more secure, the effect is the same.

08:00. We, again, disengage the cylinder. 09:00. Amelie paddles into shore and hands our problem to Ernesto. 12:00. The cylinder comes back. 1200 pesos (about $120). 13:00. The cylinder, re-installed, is taking pressure and, for the first time in about a month, the rigging seems solid. Amelie lets out a loud whoop, we slap a high five, and with one more problem solved I'm sure that a dozen more, swarming within the boat, were waiting to pop out, following in tight formation, like bees that leave a hive. We will send them out, to fend for the hive, keeping hurricanes and winged monkeys at bay. Until that time, we'll enjoy our solar-powered christmas lights that the wife found. |

|

POSTNOTE: A fateful call at 4am yanked us from our trip and onto a plane for France. Death in the family. We'll resume in February, or something.